This page is a sub-page of our page on Music.

///////

Related KMR pages:

• The Logarithmic Piano

• Pythagorean Intervals

• Uniformisation of Intervals

• Instantiations of Solfege in different Keys

• Diatonic Harmony and Pentatonic Melody

• Abstract and Concrete Chord Circles

• Interactions of Quarts and Quints

• Chord Ladder

• Transposition of Key = Shift of Basis in Music

In Swedish:

• Bengt Ulin om Musik

///////

Other relevant sources of information:

• What Is Solfege?

• Solfege: A Beginner’s Guide

• Solfège, at Wikipedia

• Solmization, at Wikipedia

• Diatonic Scale, at Wikipedia

• Diatonic and chromatic, at Wikipedia

• Modes and Scales in Western Music, at Wikipedia

• Sight Singing Techniques : How to Sight Sing Using Solfege, at Expertvillage

• Piano-ology: Solfege Recognition: An Ear Training Idea, Piano-ologist (on YouTube)

• 5 Best Android Ear Trainer Apps For Musicians

• Movable Do and Fixed Do: What they are, what they aren’t…

In German:

• Beerli, Kraus & Rinderer (1968): Von der Musik und ihren grossen Meistern

In Swedish:

• Ackord på Musikipedia

• Pianoaccord – ackordfinnare på Musikipedia.

///////

In German:

/////// Quoting Beerli, Kraus & Rinderer (1968 s. 6-12):

MELODIEKUNDE (in German)

Eine geordnete und zu einer sinnvollen Einheit zusammengefügte Tonfolge ergibt eine Melodie. Ihr Hauptmerkmal ist Bewegung, strömende kraft.

PENTATONIK

[…]

Fünftonreie ohne Halbtonschritte

Melodien dieser Art entbehern der Halbtonschritte, so daß eine halbtonlose Fünftonreie entsteht. Je nachdem, welcher Ton dieser Reihe als Hauptton (Zentralton) für eine Melodie gewählt wird, sind im Rahmen der Pentatonik verschiedene Tonarten möglich, die alle nicht auf einen Schwerpunkt (Grundton) bezogen sind; das Fehlen von Leittönen (Halbtonschritten) gibt dieser Fünftonmelodik, der Pentatonik, etwas Schwingendes, den Character des Weiten, Unendlichen.

Notenbeispiel: Eine pentatonische Reihe (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) entsteht, wenn fünf benachbarte Quinten in den Raum einer Oktave verlegt werden.

Die Pentatonik ist ein Grundsystem, das sich schon bei den ältesten Kulturvölkern (Chinesen, Griechen, Kelten) findet; pentatonische Weisen begegnen uns auch im Choral, im alten Kirchen- und Volkslied, häufig auch im echten Kinderlied und im neuen Lied.

Liedbeispiele:

• Auld lang syne

• Maienzeit bannet Lied

• Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

[…]

Die Kirchentonarten (mittelalterliche Tongeschlechter)

Die Kirchentonarten verwenden keine Vorzeichen, daher verändert sich die Lage der Halbtonschritte e-f und h-c und damit auch der Klangcharakter bei jeder Art des Tongeschlechts.

Gegenüber dem späteren Dur-Moll system, das nur noch zwei verschienen Skalen (Tongeschlechter) kennt (eben Dur und Moll), waren die Kirchentonarten wesentlich vielgestaltiger in ihrem melodischen Ausdrück; daher werden dir Kirchentonarten wieder häufig in der Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts verwendet. (–> seite 12)

[…]

Nicht nur der gregorianische Choral, auch das deutsche geistliche und weltliche Volkslied des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts stehen oft in Kirchentonarten (siehe die vorigen Beispiele sowie das Kreutzfahrerlied, Seite 46). Auch das Lied der Gegenwart greift gern auf diese mittelalterliche Tonalität zurück.

/////// End of Quote from Beerli, Kraus und Rinderer

In Swedish:

/// Skalafinnaren – Musikipedia/kyrkotonarterna.

In English:

/////// Quoting Wikipedia / Diatonic scale:

In western music theory, a diatonic scale is a heptatonic scale that includes five whole steps (whole tones) and two half steps (semitones) in each octave, in which the two half steps are separated from each other by either two or three whole steps, depending on their position in the scale. This pattern ensures that, in a diatonic scale spanning more than one octave, all the half steps are maximally separated from each other (i.e. separated by at least two whole steps).

/////// End of Quote from Wikipedia / Diatonic scale.

NOTE: By the term solfege in this context, we mean movable solfege.

///////

MODES AND SCALES IN WESTERN MUSIC

/////// Quoting from the International Chorus Bulletin:

A common misunderstanding of the ““movable \, d_o ” system is that the tonic note is always called \, d_o . This opinion, held by many poorly informed critics of the system, is likely responsible for the erroneous belief that “movable \, d_o ” is not suited to “complex” music.

In order to unburden ourselves of this error, it should be made clear that, in the “movable \, d_o ” system, the names do not impose any hierarchy with respect to scale degrees. In other words, the solfa names are nothing more than reminders of the intervallic relationships between the various notes. To put this another way, one need only generate the seven well-known modes, as follows:

Scale type \qquad \qquad \, Tonic note (Note “#1”)

“Major” (Ionian) \qquad \qquad d_o \,

Dorian \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad \; r_e \,

Phrygian \qquad \qquad \qquad \; m_i \,

Lydian \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad \, f_a \,

Mixolydian \qquad \qquad \quad \;\;\, s_o \,

“Minor” (Aeolian) \qquad \quad \;\; l_a \,

Locrian \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad t_i \,

What we see above is that, for one thing, the “natural minor” scale, i.e., the official “relative minor”, uses \, l_a \, as its tonic. Even for individuals raised more or less exclusively on a diet of major-minor music, it can require some mental discipline to hear \, l_a \, as the tonic note, and to hear \, d_o \, as the minor third of that scale. Beyond these two, basic to most students whose experience with the Western tradition is often confined to music written post-1700, the remaining modes may require even more substantial perceptual overhauls at the outset. For instance, in the Phrygian scale, \, d_o \, functions as the flattened sixth degree, and so on.

/////// End of Quote from the International Chorus Bulletin.

///////

\, \begin{matrix} T_{onarten} & ~ & H_{auptton} & H_{erschton} \\ & & & \\ I_{onian} & ~ & d_o & s_o \\ D_{orian} & ~ & r_e & l_a \\ P_{hrygian} & ~ & m_i & d_o \\L_{ydian} & ~ & f_a & d_o \\ M_{ixoLydian} & ~ & s_o & r_e \\ A_{eolian} & ~ & l_a & m_i \\ L_{ocrian} & ~ & t_i & ~ \end{matrix} \,///////

Musical Modes and Scales:

NOTE 1: An interval between two consecutive red notes represents a half-tone-step. Any other interval, i.e., any interval that contains at least one non-red note, represents a whole-tone-step (= two half-tone-steps).

NOTE 2: The expression \, (mod \, 7) \, in the formulas below refers to “counting modulo seven”, which means “not distinguishing between multiples of seven.” If we are counting modulo seven, we have \, 7 \, = \, 0 \, , \, 8 \, = \, 1 \, , \, 9 \, = \, 2 \, , \, 10 \, = \, 3 \,, etc.,

since each right-hand side differs from its left-hand side by a multiple of \, 7 .

“Counting modulo some number” is an example of applying modular arithmetic.

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, {N_{ote} n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 7)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\ & & & & & & & & & \\ I_{onian} = M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \\ D_{orian} & ~ & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e \\ P_{hrygian} & ~ & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & m_i \\L_{ydian} & ~ & f_a & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} \\ M_{ixoLydian} & ~ & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o \\ A_{eolian} = M_{inor} & ~ & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a \\ L_{ocrian} & ~ & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & t_i \, \end{matrix} \,/////// Linking to Wikipedia:

• Ionian mode

• Dorian mode

• Phrygian mode

• Lydian mode

• Mixolydian mode

• Aeolian mode

• Locrian mode

/////// Interval-based:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, {I_{nterval}}_{(mod \, 7)} \, \rangle & ~ & 01 & 12 & 23 & 34 & 45 & 56 & 67 & 78 \\ & & & & & & & & & \\ I_{onian} = M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e \\ D_{orian} & ~ & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i \\ P_{hrygian} & ~ & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} \\L_{ydian} & ~ & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o \\ M_{ixoLydian} & ~ & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a \\ A_{eolian} = M_{inor} & ~ & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i \\ L_{ocrian} & ~ & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} \, \end{matrix} \,///////

[ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{I_{onian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \, { \rangle }_{I_{onian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{D_{orian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e \, \, { \rangle }_{D_{orian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{P_{hrygian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & m_i \, \, { \rangle }_{P_{hrygian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{L_{ydian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, f_a & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} \, \, { \rangle }_{L_{ydian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{M_{ixoLydian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o \, \, { \rangle }_{M_{ixoLydian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{A_{eolian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a \, \, { \rangle }_{A_{eolian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{L_{ocrian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & t_i \, \, { \rangle }_{L_{ocrian}} \, \end{matrix} \,///////

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, N_{ote} {n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 7)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\ & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \\ M_{inor} & ~ & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a \, \end{matrix} \,/////// Interval-based:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, {I_{nterval}}_{(mod \, 7)} \, \rangle & ~ & 01 & 12 & 23 & 34 & 45 & 56 & 67 & 78 \\ & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e \\ M_{inor} & ~ & l_a t_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i d_o} & d_o r_e & r_e m_i & \textcolor{red} {m_i f_a} & f_a s_o & s_o l_a & l_a t_i \end{matrix} \,Parallel major and minor keys:

Since \, I_{onian} = M_{ajor} \, and \, A_{eolian} = M_{inor} \, we have the following representations of the diatonic major (= “dur”) and diatonic minor (= “moll”) scales:

[ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{M_{ajor}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \, { \rangle }_{M_{ajor}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{M_{inor}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a \, \, { \rangle }_{M_{inor}} \, \end{matrix} \,Harmonic and Melodic Minor:

//// TO BE ADDED

///////

Mapping out the full 12-half-tone diatonic major and minor scales

/////// Quoting Wikipedia/Modular Arithmetic/Applications:

In theoretical mathematics, modular arithmetic is one of the foundations of number theory, touching on almost every aspect of its study, and it is also used extensively in group theory, ring theory, knot theory, and abstract algebra. In applied mathematics, it is used in computer algebra, cryptography, computer science, chemistry and the visual and musical arts.

[…]

In music, arithmetic modulo 12 is used in the consideration of the system of twelve-tone equal temperament, where octave and enharmonic equivalency occurs (that is, pitches in a 1∶2 or 2∶1 ratio are equivalent, and C-sharp is considered the same as D-flat)

/////// End of Quote from Wikipedia

Let us review the diatonic major scale described above:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, N_{ote} {n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 7)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\ & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \end{matrix} \,If we denote each position \, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 \, in the above order of the columns by the number of half-tone steps it takes to reach it from the position \, d_o \, in the diatonic major scale \, d_o, r_e, \textcolor{red} {m_i}, \textcolor{red} {f_a}, s_o, l_a, \textcolor{red} {t_i}, \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, , we get the list \, 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12 \, , where we must now count “modulo 12”, i.e., \, 12 = 0, \, 14 = 2, etc., since tones that differ by multiples of 12 denote the same note on any 12-half-tone scale.

Hence we can write:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, N_{ote} {n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 12)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 2 & 4 & 5 & 7 & 9 & 11 & 12 \\ & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \end{matrix} \,and, if we fill in the missing half-tones, we get the full 12-half-tone diatonic major scale:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, N_{ote} {n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 12)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 \\ & & & & & & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o & d^{ \, \#}_o & r_e & r^{ \, \#}_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & f^{ \, \#}_a & s_o & s^{ \, \#}_o & l_a & l^{ \, \#}_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \end{matrix} \,Moreover, on any 12-half-tone diatonic scale, we have the equality \, l^{ \, \#}_a \, \equiv \, t^{ \, b}_i \, and for structural reasons that will become clear later, the expression \, t^{ \, b}_i \, is normally used here.

Hence, we get the most common representation of a 12-half-tone diatonic major scale:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, N_{ote} {n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 12)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 \\ & & & & & & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{ajor} & ~ & d_o & d^{ \, \#}_o & r_e & r^{ \, \#}_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & f^{ \, \#}_a & s_o & s^{ \, \#}_o & l_a & t^{ \, b}_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \end{matrix} \,The corresponding (so-called “parallel”) 12-half-tone diatonic minor scale is given by:

\, \begin{matrix} \langle \, M_{ode} \, || \, N_{ote} {n_{umber}}_{(mod \, 12)} \, \rangle & ~ & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 \\ & & & & & & & & & & & & & & \\ M_{inor} & ~ & l_a & t^{ \, b}_i & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & d^{ \, \#}_o & r_e & r^{ \, \#}_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & f^{ \, \#}_a & s_o & s^{ \, \#}_o & l_a \, \end{matrix} \,///////

[ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{I_{onian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, d_o & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, \, { \rangle }_{I_{onian}} \, \end{matrix} \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{A_{eolian}} = \, \begin{matrix} \langle \, \, l_a & \textcolor{red} {t_i} & \textcolor{red} {d_o} & r_e & \textcolor{red} {m_i} & \textcolor{red} {f_a} & s_o & l_a \, \, { \rangle }_{A_{eolian}} \, \end{matrix} \, \, ( \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{I_{onian}} \, , [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{A_{eolian}} \, ) \, = \, ( \, [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{M_{ajor}} \, , [ \, d_{iatonic}s_{cale} \, ]_{M_{inor}} \, ) \, = \, \, = \, ( \, \langle \, d_o r_e \textcolor{red} {m_i} \textcolor{red} {f_a} s_o l_a \textcolor{red} {t_i} \textcolor{red} {d_o} \, { \rangle }_{M_{ajor}} \, , \, \langle \, l_a \textcolor{red} {t_i} \textcolor{red} {d_o} r_e \textcolor{red} {m_i} \textcolor{red} {f_a} s_o l_a \, { \rangle }_{M_{inor}} \, ) \, \, C_{hord}S_{equences} \,\,\, \xrightarrow[]{ \,\,\, ( \, [ \, \cdot \, ]_{M_{ajor}} \, , \, [ \, \cdot \, ]_{M_{inor}} ) \,\,\, } \,\,\, C_{hord}S_{equences} \, \, C_{hord}S_{equences} \, \ni \, c_{hord}s_{equence} \xmapsto{ \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\, } ( \, [ \, c_{hord}s_{equence} \, ]_{M_{ajor}} \, , \, [ \, c_{hord}s_{equence} \, ]_{M_{inor}} ) \, \in \, C_{hord}S_{equences} \,///////

The Group Structure of Musical Intervals

Definitions:

Every square of a note is equal to 1:

\, d^2_o = r^2_e = m^2_i = f^2_a = s^2_o = l^2_a = t^2_i = 1 \,

Multiplication of intervals:

\, (d_o r_e) (r_e m_i) = d_o r_e r_e m_i = d_o m_i \,

\, (d_o m_i) (m_i f_a) = d_o m_i m_i f_a = d_o f_a \,

\, (d_o f_a) (f_a s_o) = d_o f_a f_a s_o = d_o s_o \,

\, (d_o s_o) (s_o l_a) = d_o s_o s_o l_a = d_o l_a \,

\, (d_o l_a) (l_a t_i) = d_o l_a l_a t_i = d_o t_i \,

These equations present a group \, G(d_o, r_e, m_i, f_a, s_o, l_a, t_i) ,

whose inversive structure can be summarized in the following multiplication table:

Note: The expression \, \log \, below refers to \, {\log}_2 \, , which means logarithms with base \, 2 . Hence we have the identities \, 2^{\log x} \, \equiv \, 2^{{\log}_2 x} \, \, \equiv \, x .

On an equally tempered 12-tone scale, such as the one employed by the piano,

we therefore can write:

Hence we can conclude that

\, \log m_{ajorThird} \, = \, \frac{4}{12} \, , \log q_{uart} \, = \, \frac{5}{12} \, , \, \log q_{uint} \, = \, \frac{7}{12} \, ,

and therefore, for example:

\, q_{uart} * q_{uint} = 2^{ \, \log q_{uart} \, + \, \log q_{uint} } = 2^{ \, \frac{5}{12} \, + \, \frac{7}{12} } = 2^{ \, \frac{12}{12}} = 2^{ \, 1} = 2 = o_{ctave} \, ,

which is the musicological term that denotes this interval.

///////

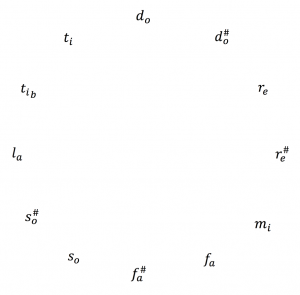

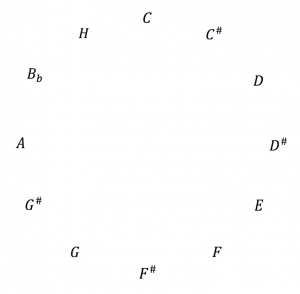

The abstract half-tone circle for 12-tone diatonic music:

\, \langle \, d_o \, d_{o}^{\#} \, r_e \, r_{e}^{\#} \, m_i \, f_a \, f_{a}^{\#} \, s_o \, s_{o}^{\#} \, l_a \, t_{i_b} \, t_i \, \rangle_{Sol} \,The abstract half-tone circle instantiated in d_o := C \, :

/////

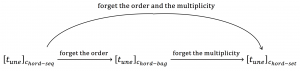

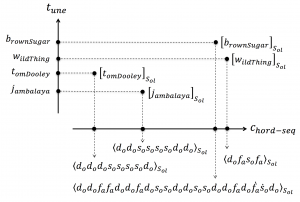

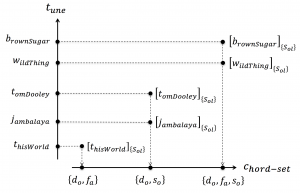

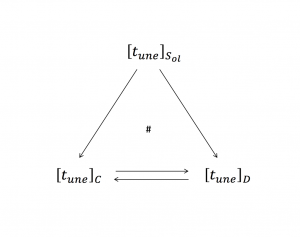

Let \, {[ \, t_{une} \,]}_{chordSeq} \, denote an equally beated \, c_{hordSequence} \, for the \, t_{une} \, . Forgetting the order of the chords gives the \, c_{hordBag} \, for the \, t_{une} \, , and forgetting the multiplicities of the chords in the bag gives the \, c_{hordSet} \, for the \, t_{une} \, . Hence we have:

\, {[\, t_{une} \,]}_{chordSeq} \xrightarrow{ \,\, forget \; the \; order \,\,} {[\, t_{une} \,]}_{chordBag} \xrightarrow{\,\, forget \; the \; multiplicity \,\,} {[\, t_{une} \,]}_{chordSet} \,///////

\, {[ \, j_{ambalaya} \, ]}_{S_{ol}} \, = \, {\langle \, d_o \, d_o \, s_o \, s_o \, s_o \, s_o \, d_o \, d_o \, \rangle}_{S_{ol}} \, \, {[ \, t_{omDooley} \, ]}_{S_{ol}} \, = \, {\langle \, d_o \, d_o \, d_o \, s_o \, s_o \, s_o \, s_o \, d_o \, \rangle}_{S_{ol}} \, \, {[ \, j_{ambalaya} \, ]}_{\{{S_{ol}}\}} = {[ \, t_{omDooley} \,]}_{\{{S_{ol}}\}} \, = \, {\langle \, \{ \, d_o, s_o \, \}\rangle}_{\{{S_{ol}}\}} = \{ \, d_o, s_o \,\} \,///////

{[ \, w_{ildThing} \,]}_{S_{ol}} \, = \, {\left< \, d_o \, f_a \, s_o \, f_a \, \right>}_{S_{ol}} \, {[ \, w_{ildThing} \,]}_C \,\, = \,\, {\left< \, C \, F \, G \, F \, \right>}_C \, {[ \, w_{ildThing} \,]}_G \,\, = \,\, {\left< \, G \, C \, D \, C \, \right>}_G \,///////

///////

///////

///////

The tune “The Entertainer” (by Scott Joplin) represented in “piano coordinates”:

In German:

/////// Quoting Beerli, Kraus & Rinderer (1968 s. 33-34):

RHYTMUS – TAKT:

Zwei Merkmale bestimmen eine Melodie:

1. Die Aufeinenderfolge gleich hoher oder verschieden hoher Töne (Höhenlinie).

2. Die Aufeinenderfolge gleich langer oder verschieden langer Töne (Rhythmus).

Höhenlinie und Rhythmus sind unabhängig voneinender; die gleiche Höhenlinie kann verschieden rhythmisiert werden:

////// Beispiel

Für den Rhythmus ist die betonung der einzelnen Töne wichtig.

Die regelmäßige Wiederkehr gleichartig betonter Rhythmen shafft den Takt.

Takt ist die Aufeinenderfolge eines schweren (betonten) Taktteils

und eines oder mehrerer leichter (unbetonter) Taktteile.

Die beiden Urformen metrischer Gliederung

sind der gerade und der ungerade Takt.

(Metrum, griech. metron = Maß)

Zweischlag ist Schreiten

Dreischlag ist Springen:

Oft werden gute Taktteile überbelastet: punktierter Rhythmus.

Durch die Synkope wird ein sonst unbetonter Taktwert überraschenderweise betont.

Die synkope ist Ausdrucksmittel für Spannung, Erregung, Überraschung, sie will besonders eindringlich sprechen. Sehr bewegte Zeiten bedienen sich besonders gerne der Synkope (zeitgenössische Musik, Jazz!).

Rhythmus ist ein Urelement der Musik, eine innerhalb des metrischen Gleichmaßes von innen wirkende Kraft; sie bewirkt den Wechsel von Spannung und Lösung, der die Tonfolge einerseits in kleine Einheiten (Takte) ordnet, anderseits diese wieder zu größeren Einheiten gliedert und zur Gesamtgestalt zusammenfaßt.

Der Begriff “Rhythmus” ist jenem des “Taktes” übergeordnet.

Die ältere und auch die neue Musik kennen den lebendigen Wechsel von Zwei- oder Drei-schlag. Aus dem Wesen dieses freien Rhythmus ergibt sich, daß diese Tonfolgen nicht metrisch gemessen und daher oft ohne Taktstriche notiert werden. Wenn dabei zur besseren Orientierung und Übersicht der Taktstrich beibehalten wird, entsteht ein buntes Bild häufigen Taktwechsels.

/////// End of Quote from Beerli, Kraus und Rinderer

Back to English:

///////

Hello. remarkable job. I did not expect this. This is a splendid story. Thanks!

Thanks Jack! These music pages are still very much under construction. For example, the page called Harmony an Melody still lacks a text that will describe my methodology to learn to play pentatonic “improvisation piano” based on a sequence of diatonic chords on the x-axis and, for each chord, the pentatonic melodical choice-possibilities (whenever this cord is active) on the y-axis. I have used myself as a test-pilot for this methodology, and (I think that) I have made substantial progress using it.

Best regards

/Ambjörn

Very well written information. It will be valuable to anyone who utilizes it, including me. Keep doing what you are doing – can’r wait to read more posts.

Thanks Rose, I’m glad that you find my writings on the connections between mathematics and music helpful. I often think of these connections as a two way street. Moving one way is ‘musemathics’ where you can learn more about mathematics through music and moving the opposite way is ‘mathemusic’ where you can learn more about music through mathematics.

These are truly fantastic ideas in regarding blogging. You have touched some good points here. Any way keep up writing.